Clear governance makes digital issues visible and actionable. When responsibilities are clearly defined—from political oversight to management and technical teams—problems can be identified early, addressed at the right level, and escalated when necessary.

This page explains, in practical terms, how control works in complex government digital systems. Based on real-world experience, it shows how technical, organizational, and legal factors interact, helping decision-makers plan, govern, and exercise effective oversight.

Understanding people and roles in digital governance

Digital governance thrives on the interaction between skilled specialists and effective managers. Specialists respond best when issues are framed in a real-world context — not just technically, but situationally. They are activated by complex technical ambiguity and challenged by autonomy, technical career paths, and meaningful recognition.

Managers add value beyond the technical peak, especially as IT challenges outpace traditional education. They are activated by organizational complexity and challenged by strategic influence, ownership, and outcome-based incentives. Face-to-face communication with skilled employees is the only practical way for a manager to work through demanding issues, translate technical challenges into business impact, and perform the necessary post-mortem analysis. Many managers reach their role after struggling with the work themselves, making guidance, collaboration, and effective platforms essential for real progress.

This balance of expertise and guidance transforms IT’s technical challenges into expected results.

Moving beyond isolated IT

In business administration, many concepts act as abstract endpoints — guiding yet never fully tangible, unlike accounting rules. Progress will stop if input does not go beyond the sandbox function. Complex challenges demand strategic accountability — guiding collaboration before technical or legal execution, yet avoiding unnecessary steering.

Standards and global positioning

Digital standards become clear through targeted, accessible training materials.

A Dutch expert group can play a pivotal role in aligning global digital developments.

Identity and digital infrastructure

WebIDs are still evolving — a name such as ‘Peter Jansen’, ‘P. Jansen,’ or ‘P Jansen’ cannot serve as a unique identifier.

Strategic guidance and domain awareness – for discussion

Centralized digital governance is increasingly recognized as critical for successful transformation. Klöpping and Blom (2023), among others, highlight that fragmented responsibilities slow down progress and reduce effectiveness. One option often raised is the creation of a separate Ministry for Digital Affairs. Yet such a ministry may lack the weight of long-established portfolios like Finance, and risks becoming another silo. An alternative worth considering is to position NL Digital Framework Council within the Ministry of General Affairs. This would place digital governance at the core of cabinet coordination, ensuring strategic direction at the highest level, while leveraging existing financial and administrative expertise.

If chosen, this approach enables:

– Real progress through established ticketing systems and procedures, driven by clear formulation and an escalation path for decisive action;

– A coherent national digital strategy, with centrally defined standards and priorities;

– Clear accountability, while individual ministries remain responsible for domain-specific implementation (e.g., healthcare, housing, justice).

Strategic key topics

1. Governance & Transparency

- International-first design — Government digital solutions should be designed for interoperability across borders. Systems must not be restricted to local contexts, ensuring resilience and adaptability to international standards.

- User-level English — For user-level flexibility, U.S. English should be supported; for example, in services such as rdap.org.

- Legal and normative language — Legal and normative prescriptions and clarifications from the NL Standardization Forum shall be written in U.S. English, ensuring consistency with international standards and accessibility for global developers.

- Transparent tariffs and charges — Monopoly tariffs, charges, and discounts should be explicitly assessed, centrally validated, and published in the public interest. This ensures justified pricing and prevents hidden costs.

- Early legal frameworks — Establish clear legal structures to guide and support maturing projects from the outset. Governance should evolve alongside technical maturity, providing stability without stifling innovation.

- Addressing quality behaviours — such as correct time-outs — is the starting point for proven tools to take over meaningfully.

- Cross-ministerial governance — Governance is effective only when it transcends ministerial boundaries, backed by binding standards that enable operational efficiency rather than strategy in name only.

2. Infrastructure & Domain Management

- Registrar Rijksoverheid: Government domains should be registered under a clearly identifiable registrant name with an accountable contact person. Anonymous or unclear registration reduces trust and accountability, and makes it too difficult to determine responsibility when issues arise between interconnected systems.

- Direct registrar relationships: Government domains should be managed exclusively through direct registrar relationships. Use of domain resellers introduces unacceptable risks of mismanagement, fragmentation, and lack of accountability.

- Third-level domain readiness: an example.gov.nl requires direct accountability without multi-step lookups, and SIDN can accelerate a dedicated .gov.nl policy if the government makes this choice.

- SOA RNAME mailbox compliance: Authoritative nameservers should comply with RFC 2142 and RFC 1035 by ensuring a functioning and monitored RNAME mailbox. This guarantees reliable contactability in case of incidents.

- Reverse server name accountability: Reverse server name domains should unambiguously resolve to the server or service responsible for the corresponding address space. This could become a MUST to strengthen accountability and transparency.

- Nameserver registration holder transparency: Each nameserver domain should have a visible and transparent business owner. Public clarity on responsibility strengthens both operational resilience and trust.

- Whois and RDAP usage: TLD terms should no longer hinder the analysis of business relationships.

3. Tools & Operational Capability

- First-contact accountability with ticket-based escalation —

A structured, integrated ticketing system supports this process by enabling knowledge sharing, ensuring the legal traceability of third-party submissions (such as screenshots or other evidence), and providing a formal channel for enhancement requests directed to delivering organizations. Accountability remains with the first point of contact, preventing unnecessary burden on citizens, while continuous improvement is built into the workflow.- Public-interest disclosures must be receivable without forced procedural or contractual consent.

(Global basis: UNCAC Art. 33 — Protection of reporting persons)- Civil-servant ownership of incoming issues —

“Your request concerns matters that fall under the responsibility of another competent authority. That authority applies existing and functioning requirements in this area. Your request will therefore be forwarded to the appropriate authority for further handling.”- Mature vulnerability management —

Integrate issue-source analysis and regular maintenance to distinguish configuration or quality findings from genuine security vulnerabilities.- Integrated RDAP tooling —

Assign responsibility for RDAP implementation to the government itself. The registry (SIDN) is not accountable for service delivery; instead, government-owned RDAP services ensure alignment with governance, transparency, and international obligations.- Automated audit tools —

Equip the Data Officer with advanced automated mechanisms to verify or revoke registrant validations. This reduces dependency on impractical manual workloads while maintaining compliance, oversight, and the ability to act decisively in the public interest.- Naming Standardization in the Trade Register —

– Abbreviations should be normalized — for instance, “B.V.” and “N.V.” are to be standardized as “BV” and “NV” in a newlegalized_namefield of the Trade Register.

– Case sensitivity must be enforced, requiring the register to treat uppercase and lowercase letters in trade names as distinct legal identifiers.

– Primary trade name designation — the Trade Register shall explicitly record, in a separate table, which trade name (with aprimary_fromUTC date-time) is designated as the primary trade name for each registered entity. If only one trade name is registered, it shall automatically be primary. Where multiple trade names exist, exactly one must be primary. For an eenmanszaak, at least one trade name shall exist, and exactly one must be primary. For a B.V. or N.V., if no trade name is registered, thelegalized_nameshall serve as the trade name and be primary.

E.g.: legal name: ‘SIDN B.V.’; legalized name: ‘SIDN BV’; trade name (s): ‘SIDN’; primary name: ‘SIDN’4. International & Security Alignment

- EU cloud direction: governance and direction should be tested at a small scale before committing to large-scale investments. Early experimentation reduces lock-in and ensures better alignment with European frameworks.

- ICANN/IANA maturity: strengthen TLD support with more relevant machine-readable data and structures, ensuring Dutch domains remain interoperable and aligned with international standards.

- ICANN design test: continuously assess ccTLD-proof tables and access structures to validate robustness against international technical and governance requirements.

- Automated country-level security test: implement automated detection of risks based on validated domain and URL lists, saving time and enabling faster, more reliable security responses at scale.

- National data centers: assign clear administrative roles and responsibilities for national data centers to ensure capable civil service performance and sustainable, sovereign infrastructure.

Regarding Web Domain and Hosting Control:

The Dutch website internet.nl (en.internet.nl), a Django-based application, provides valuable action points for responsible parties based on automated test results. However, several structural and conceptual aspects deserve closer attention:

- Score weighting limitations — Because internet.nl covers a broad range of test topics, a serious issue may result in only a small score deduction within an otherwise high overall percentage. In practice, this can obscure real problems behind near-perfect scores.

- Inaccessible services can still score well — Web or mail services that are closed or unreachable can still achieve scores of approximately 61% (web) or 70% (email) based solely on DNS configuration, despite the service itself being unusable.

- Time-outs should count as hard failures — Time-outs are often treated as temporary conditions. From a user perspective, however, a time-out means the service is unreachable. In that sense, a time-out is as critical as missing HTTPS or broken redirects and should be handled as a hard failure.

- Domain holder name checks are complex — Verifying domain registration holder names depends heavily on country-specific rules. While most technical components exist, meaningful progress also requires regulatory and political alignment, not just technical solutions.

- “Hall of Fame” may need rethinking — The current Hall of Fame concept works well today, but may require more future-proof criteria, such as ownership or control validation through email-based identification.

- Separate IPv4/IPv6 and www results — IPv4, IPv6, www, and non-www configurations are frequently not identical. Presenting results in four separate columns makes these differences immediately visible and easier to interpret.

- Email scores can be misleading — Email delivery and reception depend on many external factors. A 100% email score may suggest completeness, while real-world behavior can still differ significantly.

- Public display of (sub)domains — Publishing 100% test results for (sub)domains can lead to unwanted or unsolicited contact. For this reason, public display of such results should be carefully reconsidered.

- Create a second table and processing structure suitable for the interface, including email fields —

• result_id – database technical id

• domain – identifier (sub)domain without a leading “www.”

• protocol – identifier ipv4 / ipv6

• www – identifier without_www / with_www

• requested_at – for request identification

• started_at – retrieval time initialization

• finished_at – retrieval time calculation

• action_points – including urgency descriptors

• … (existing fields)

From Actionable Screenshots to Resolution and Management-Ready Post-Mortem Reviews

- Free Domain Lookup, including DNSSEC and Whois (PHP/Python/JSON, since August 15, 2021) — rdap.hostingtool.nl/modeling_domain

- Free Server Header Lookup (replaced design PHP/XML, since January 14, 2022) — www.hostingtool.nl/server_headers

- Testing receipt of email with a false sender (PHP/SMTP, since June 25, 2022) — not a public tool

- Free Domain Control Register ® (PHP/JSON, since November 30, 2024) — www.domaincontrolregister.org

- Free Homepage Route Overview (PHP/Python, since February 26, 2025) — www.workingornot.org

- Free Security Header Overview (PHP/Python, since March 18, 2025) — securityheaders.hostingtool.org

- Free Hosting Lookup (PHP/Python/JSON, since May 6, 2025) — lookup.hostingtool.org

- Free Registry Table Definition Design (PostgreSQL, since May 16, 2025) — github.com

- Free Top-level Domain Lookup (PHP/JSON, since June 21, 2025) — rdap.hostingtool.nl/modeling_tld

- Free Mail Exchange Analysis (PHP/Python, since March 2, 2026) — analyzemx.hostingtool.org

- Free Hybrid Crypto Analysis (PHP/Python, since March 2, 2026) — analyzetls.hostingtool.org

Towards a Tri-Partite and Parallel Structure for Digital Governance in the Netherlands

Principle of Functional Separation

Effective digital governance requires ongoing normative work alongside coordination. Governance cannot rely solely on steering or project-based alignment; it requires a continuously developed normative framework that defines roles, responsibilities, and architectural conditions.

Clear functional separation between policy/advisory mandates and operational service delivery is essential. Advisory bodies should not assume execution tasks, and execution should not determine its own normative boundaries. Operational responsibilities — such as DigiD and MijnOverheid under the Logius Agency — remain with their designated service organisations.

Following the recent evaluation of the Netherlands’ Digitalisation Strategy (NDS), it is evident that the current structure lacks durable institutional anchoring and clear functional layering. Strengthening digital governance therefore requires a structural distinction between strategic, tactical, and operational mandates.

Operational (Digitale Kenniswisseling) → Tactical (Orgaan Digitale Expertise) → Strategic (Nationale Raad voor Digitale Kaders / Forum Standaardisatie) → Cabinet

Mandates under the Ministry of General Affairs

Nationale Raad voor Digitale Kaders — nationaledigitalekaders.nl — NL Digital Framework Council

Composed of former politicians and strategic thinkers. Body mandate:

- Validates and formalizes expert authority in digital affairs.

- Identifies and assesses strategic issues of national importance.

- Determines escalation to the Cabinet for unresolved or high-impact matters.

- Applies academic foresight — including scenario studies and long-term research — to strengthen national digital strategy.

Forum Standaardisatie — forumstandaardisatie.nl — NL Standardization Forum

Composed of senior civil servants. Body mandate:

- Governs and maintains national standards in digitalization.

- Initiates and coordinates the strategic design of digital governance instruments.

- Provides structured input to Nationale Raad voor Digitale Kaders where standardization issues require escalation.

Mandates under the Ministry of the Interior

Orgaan Digitale Expertise — orgaandigitaleexpertise.nl — NL Digital Expertise Body

Composed of management-level experts. Body mandate:

- Sets authoritative tactical direction to ensure cross-government digital coherence.

- Validates executability, scalability, and sustainability of digital initiatives.

- Acts where coordination fails to deliver outcomes.

- Anchors digital decisions in expert judgment.

- Eliminates duplication, fragmentation, and vendor dependency.

- Enforces architectural and data coherence across ministries.

- Escalates unresolved digital failures to NL Digital Framework Council.

- Applies scientific and academic evidence to executive action.

- Prioritises delivery capability and timely decisions.

- Ensures that digital mandates are exercised exclusively by the designated body and are not fragmented or duplicated through internal ministerial directorates.

Digitale Kenniswisseling — digitalekenniswisseling.nl — NL Digital Knowledge Exchange

Composed of civil servants. Body mandate:

- Organizes platforms differentiated by education type.

- Serves as the operational point of contact for digital knowledge within public administration and in cooperation with private companies.

- Supports the Digital Expertise Body in the execution of its mandate.

- Does not assume responsibility for service delivery, which remains with designated operational agencies (e.g. DigiD under Logius).

Parallel Body

Stichting ECP | Platform voor de InformatieSamenleving — ecp.nl — NL Platform for the Information Society

Composed of representatives from private companies, sector organizations, and societal stakeholders. Parallel body mandate:

- Provides structured, non-binding input on technological developments, market trends, and innovation relevant to national digital affairs.

- Assesses and communicates practical implications and societal effects of proposed standards, governance instruments, and policies.

- Facilitates broad stakeholder dialogue and understanding of digital developments in society.

- Contributes expertise during consultation processes initiated by Digitale Kenniswisseling, Orgaan Digitale Expertise, or Forum Standaardisatie, without decision-making authority.

- Does not exercise steering, oversight, prioritisation, or service delivery functions, which remain exclusively with public authorities and designated agencies.

This parallel mandate is consultative only and does not confer public authority, executive power, or decision-making competence.

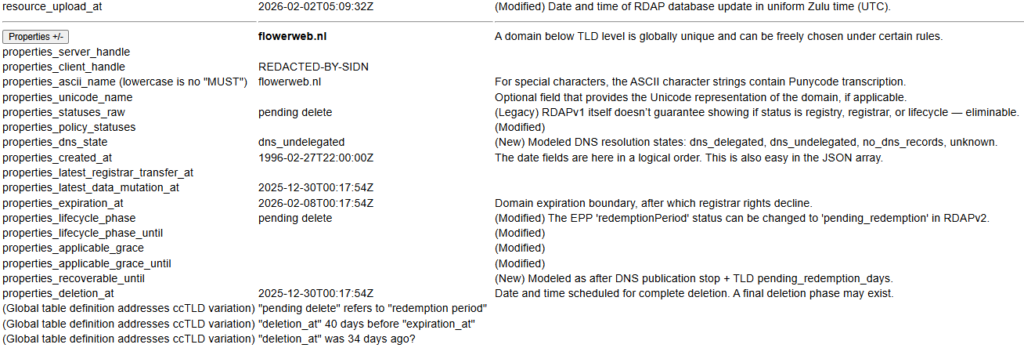

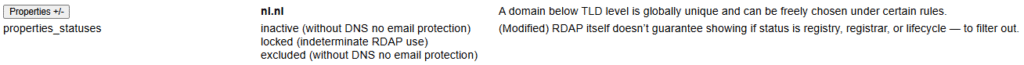

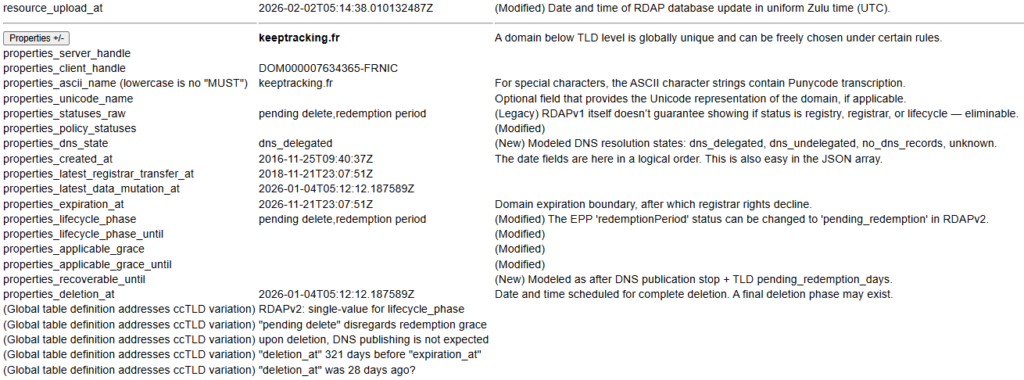

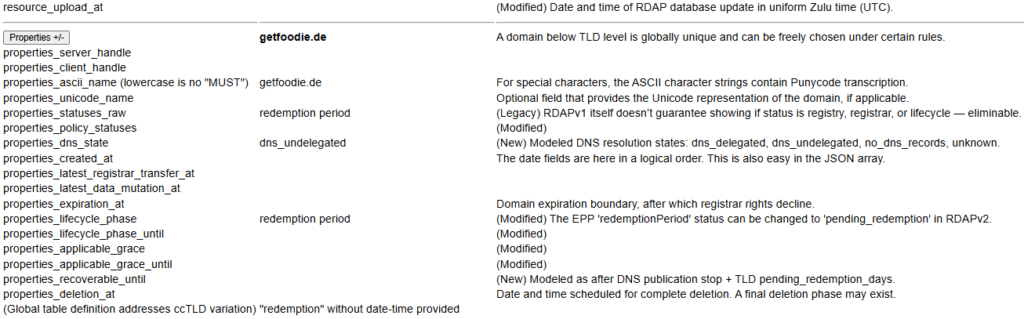

Fragmented ccTLD Systems: Why ICANN Must Address the Modeling Barrier

A proposal for “RDAP Next” — a unified, semantically consistent registry data model designed for automation, interoperability, and accountability.

- ICANN’s limited visibility into the diverse software environments powering ccTLD operations has led to systemic fragmentation — a critical obstacle to achieving unified and resilient global registry modeling.

- PostgreSQL’s support for

JSONandJSONBfield types enables flexible storage of semi-structured, TLD-specific identifier properties. These capabilities are essential for integrating heterogeneous data from multiple sources. However, the current RDAPvCardarray format for postal addresses lacks structural consistency. For example, inconsistent use of country names versus ISO codes in RDAP responses undermines both machine readability and data reliability. Flattened JSON fields eliminate arbitrary nesting and reduce schema ambiguity. - Operationally, some ccTLDs — such as the Netherlands — have implemented optimized practices, including indexed fields for postal code search. Next, RDAP output, especially for an entity nested at the table level, can be done at a single level. This facilitates both automatic parsing and user-friendly presentation. And finally, the table structure should enforce role-specific visibility in RDAP to reduce ambiguity and improve security.

- Data quality is further undermined by overreliance on registrar-supplied input. In many ccTLD ecosystems, registrars remain the primary data source, often without authoritative validation. This weakens data integrity and highlights the need for automated, standardized controls across the registry landscape.

- Domain lifecycle modeling also demands greater precision. For instance: a domain marked as

pendingDeleteshould not simultaneously carry theredemptionPeriodstatus — and vice versa. These are mutually exclusive lifecycle states that should be modeled explicitly to prevent operational ambiguity. - RDAP includes domain status codes such as transfer prohibited. However, unlike EPP, RDAP does not distinguish whether these restrictions are imposed by the registrar (client-side) or the registry (server-side). This lack of granularity and accountability having an unspecified actor may hinder operational clarity and complicate dispute resolution.

- Aligning the domain deletion phase (

pendingDelete) with search engine deindexing elevates it from a purely technical state to a GDPR-relevant lifecycle boundary. This alignment creates legal, operational, and policy incentives to support data minimization, authoritative lifecycle closure, and responsible information removal. - RDAP Next Modeling

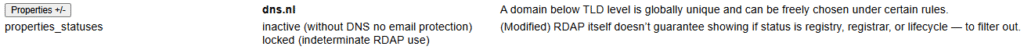

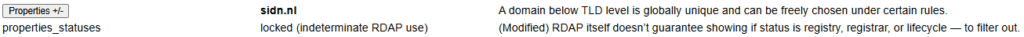

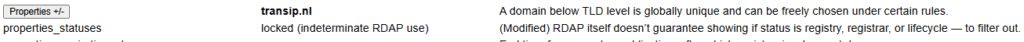

Legacy RDAP status labels are ambiguous and inconsistently applied. The proposed model introduces structured, descriptive status identifiers to ensure semantic clarity, interoperability, and consistency in automation.

RDAP Status Remapping

(in)active → dns_state (existence of a name server): dns_delegated / dns_undelegated

redemption period → pending_redemption

Prohibition Flags:

When registry-controlled:

* serverTransferProhibited

* serverUpdateProhibited

* serverDeleteProhibited

* serverRenewProhibited

Otherwise registrar-controlled:

* clientTransferProhibited

* clientUpdateProhibited

* clientDeleteProhibited

* clientRenewProhibited

Note 1: Avoid using indeterminate statuses (e.g., locked or transfer prohibited) when more fine-grained flags are available.

Note 2: If a domain has no DNS, it cannot use DMARC / SPF to defend against unauthorized email.

Finally, URL paths use kebab-case, EPP elements use camelCase, and JSON fields and query parameters from space-separated lowercase to snake_case use. Furthermore fixed-order arrays for readability, and abuse, only at table level, under the registrar.

[

{"metadata":[

{"object_type":"domain",

"zone_identifier":"nl",

"terms_and_conditions_uri":"https://rdap.hostingtool.nl/modeling_tld/?tld=nl",

"global_json_response_uri":"",

"registry_json_response_uri":"",

"registrar_accreditation":[{"type":"IANA Registrar ID","identifier":"0000"}],

"registrar_json_response_uri":"",

"resource_upload_at":"2025-11-16T00:43:55Z"}]},

{"properties":[

{"ascii_name":"example.nl",

"unicode_name":"example.nl",

"dns_state":["dns_delegated"],

"created_at":"2005-02-11T10:32:57Z",

"latest_data_mutation_at":"2025-02-07T13:03:43Z"}]},

{"entities":[

{"registrant":[{"organization_name":"Example B.V.","email":"jan@example.nl","country_code":"NL"}]},

{"reseller":[{"organization_name":"Example B.V.","email":"reseller@example.nl","country_code":"NL"}]},

{"registrar":[{"organization_name":"Example B.V.","email":"registrar@example.nl","country_code":"NL"}]},

{"registrar_abuse":[{"email":"abuse@example.nl", country_code":"NL"}]}]},

{"nameservers":[

{"ascii_name":"ns1.transip.nl"}]},

{"delegation":[

{"dnssec_signed":true,

"dnssec_data":[{"dnssec_algorithm":"13"}]}]}

]Up-to-Date PostgreSQL Registry Table Definition (Since May 16, 2025)

Developed to replace legacy registry systems and support deployment on global RDAP servers, this schema upgrade enhances data clarity, consistency, and maintainability, representing a critical step forward in modernizing the RDAP protocol.

Machine-Readable IANA Root Zone Data:

My IANA root zone data is in a renewed format, to be retrieved from a designated IANA server and relying on user activity logging—including from unidentified internet users—for issue resolution, the tool avoids unnecessary traffic, reduces system overhead, and supports traceable, efficient operations.

RFC-allowed in the .nl Domain (Netherlands)

– Dutch SIDN maintains gTLD operational requirements for .amsterdam and .politie.

– The .frl root zone (Province of Friesland) is maintained in England and has been updated.

– If SIDN adopts 30-day pending redemption plus 5-day pending delete, it could work well.

– Final-stage domains for ccTLD: https://www.catchtiger.com/nl/domeinnaam-veilingen/

or for gTLD: https://www.expireddomains.net/expired-domains/.

– The .nl nameserver domain dns.nl has no mail-related DNS, leaving it unprotected against sender spoofing.

– During a ccTLD migration (e.g., with SIDN), each registry domain should include a registrant, contact objects, and DNS settings, and must avoid using indeterminate status values. Instead, clearly defined statuses (e.g., the EPP code serverTransferProhibited) should be applied to ensure transparent registrar responsibility.

- .nl root zone – Clearer Whois (15 open and 3 realized suggestions)

- Steps for Domain Registration (35 suggestions)

- NL country – List Whois (6 suggestions)

RFC-allowed in the .fr Domain (France)

RFC-allowed in the .de Domain (Germany)

Description of Strengthening Digital Governance in the Netherlands

- A Minister for Digital Affairs Wouldn’t Be the Right Fit

A dedicated minister could signal stronger centralization, but also risks politicizing a domain that benefits from being technically driven and multi-stakeholder. Continuity, independence, and agility are often more difficult to secure within conventional ministerial portfolios. - Nationale Raad voor Digitale Kaders under the Ministry of General Affairs

Supervision of national digital activities, policies, and strategic direction could be anchored within Algemene Zaken. This would emphasize cross-governmental importance and provide independence from sectoral interests, while situating digital governance at the core of cabinet coordination.

(NL: interacting with Forum Standaardisatie, currently part of the Ministry of the Interior) - Orgaan Digitale Expertise under the Ministry of the Interior

The body could act as the primary channel for expertise within government, ensuring that digital policy and practice are consistently aligned with the public interest. By consolidating ongoing NDS-related efforts, the body would provide coherence, legitimacy, and a trusted point of contact for both government and society.

(NL: integration of the current OBDO into this structure) - Digitale Kenniswisseling under the Ministry of the Interior

A specialized task group could foster collaboration among professionals and embed adaptive expertise across all layers of government. At present, the Standardisation Forum often serves as a point of contact, but its scope is limited. Digitale Kenniswisseling could broaden this role into a cross-governmental knowledge function with structural capacity.

(NL: merger of the current PGDI and Bureau MIDO into this structure) - Nationale Raad voor Digitale Kaders as ccTLD Manager (Long-Term Vision)

Over time, CDZ could become the designated manager of the .nl country code top-level domain (ccTLD). This would require close cooperation with ICANN, as ccTLD management changes follow a global approval process. Treating .nl stewardship as a government responsibility would reinforce sovereignty over a critical national digital asset, while ensuring transparent, multi-stakeholder governance.

Dutch ccTLD and geoTLD control:

- While the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy (EZK) provides the legal framework for domain management until November 21, 2029, this authority remains primarily a policy objective rather than an operational mandate.

- In practice, operational responsibility for the .nl country-code top-level domain (ccTLD) lies with SIDN, and this arrangement is expected to continue for the foreseeable future.

- The update reflecting SIDN B.V. as the Backend Operator, effective January 1, 2023, remains pending in the IANA database. This update is a technical and procedural correction within the existing IANA framework and does not require new ICANN policy development.

- The .frl top-level domain, by contrast, is a sponsored geoTLD privately managed by FRLregistry B.V., operating independently under ICANN’s sponsored TLD provisions.

- The Ministry of Economic Affairs does not hold the necessary digital governance expertise or formal mandate to supervise registry architecture, operational design, or interoperability principles.

- Strategic oversight and coordination could therefore more appropriately transition to Nationale Raad voor Digitale Kaders under the Ministry of General Affairs (AZ), which carries the national responsibility for digital infrastructure, interoperability, and digital standards governance.

Future Direction under Nationale Raad voor Digitale Kaders

- Include variable automated task costs in the single annual registrant fee to ensure transparent, predictable pricing and alignment with digital public infrastructure principles.

- Incorporate registrar data changes into periodic registrar costs to standardize cost recovery and maintain consistent digital identity accuracy.

- Eliminate all registry discounts to uphold fair competition and avoid market distortion inconsistent with neutral digital governance.

- Abolish the distinction between “effective” and “real” to simplify registration holder models and strengthen legal clarity in digital registries.

- Reduce test scenarios for legacy statuses in upgrading operations to streamline registry efficiency and align with current digital standards.

- Check empty registration holders. Distinguish between the SIDN foundation and the private limited company SIDN B.V..

Detailed Involvement of the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Justice

- Areas of expertise: Leverage constitutional, administrative, and cybersecurity expertise to ensure lawful, accountable digital operations.

- Engage specialists: Involve experts in digital identity, data protection, and legal interoperability across public and private sectors.

- Ensure dynamic interaction: Establish inter-ministerial coordination channels that connect legal, technical, and governance perspectives.

- Decision-making: Enable informed and transparent decisions rooted in public accountability and data protection law.

Country-Based Web Domain Services (WDSs, e.g., “Webdomeindienst” in the Netherlands)

- Jurisdiction basis: The jurisdiction of a Web Domain Service (WDS) derives from the lawful use of the domain within the country of establishment, not merely the registrant of record. This principle determines the applicable national law.

- Data minimisation: Avoid central storage of sensitive personal or organizational role data (e.g., “data officer”) at the Chamber of Commerce (KVK) to reduce exposure risk.

- National verification: Allow a national entity to verify and govern organizations operating within their jurisdiction, maintaining trust and sovereignty.

- Delegated confirmation: The appointment of key roles such as data officer should be directly confirmed by the organization’s director or equivalent national authority.

Global RDAP Design and Development (Covering NL / EU / US and generic top-level domains, the next RDAP generation aims for clarity, resilience, and lawful verification)

- Discuss global design and programming of Registration Data Access Protocol software.

– For a more readable RDAP output, writeregistrar_abusefrom its current table-level position under the registrar, at the top level of entities.

– Introduce an emergency entity in RDAP to formally organize backup to get access.

– Introduce a fallback entity in RDAP to respond when registrant information is missing. - Generate web IDs that start with the ISO2 country code, for business entities and natural persons.

- Plan verification of web domain users indexed by web ID, starting with modeling in RDAP like mine.

- Use the developed Domain Control Register®, based on party that lawfully uses the domain and is decisive for determining the applicable law in the country of establishment.

– Report regarding expired HTTPS, security.txt or DANE via email. Perhaps a DCR revenue model. - Improve web domain RDAP.

– Get custom fields approved and listed for standardization.

– The top-level domain data can be further developed and made easily automatically retrievable.

– A table schema design has been developed for registry data (ready for second-level .gov.nl).

– Future global communication between databases will require improved identifier and handle design.

– Steering application development toward Django as the preferred framework.

Our Sites

- facilitating/hosting events: hostfusion.nl/

- technical documentation: webhostingtech.nl/

Communicated DNS action points with my monitoring tools

The mandatory visible registration holder at Shift2 B.V. and the Municipality Krimpenerwaard: Shift2.pdf and Krimpenerwaard

Legacy SIDN domain statuses towards global compliance: registration-SIDN.pdf

Could SIDN B.V. have mixed operational responsibility with the SIDN foundation? missing-SIDN-B.V.png

Reverse DNS stability requires monitoring at Shift2 B.V. and Logius Agency, also see

https://stat.ripe.net/resource/91.241.6.0/23#tab=dns: shift2-nl.png and Logius.png

HTTP rewriting and the “always” option in security headers to be stabilized by Shift2 B.V.,

serving about 250 government organizations: shift2-nl-security.png

IPv6 / DNSSEC upgrade and Null MX records at education provider SURF B.V.: eur-nl.png

Repeated contact about insecure mail configuration for pcextreme.nl: insecure-pcextreme-nl.png

Web browsers tolerate an incorrect setup at Province Zuid-Holland: zuid-holland-nl.png